I have worked on polar coding since I was graduate student at UIUC Math.

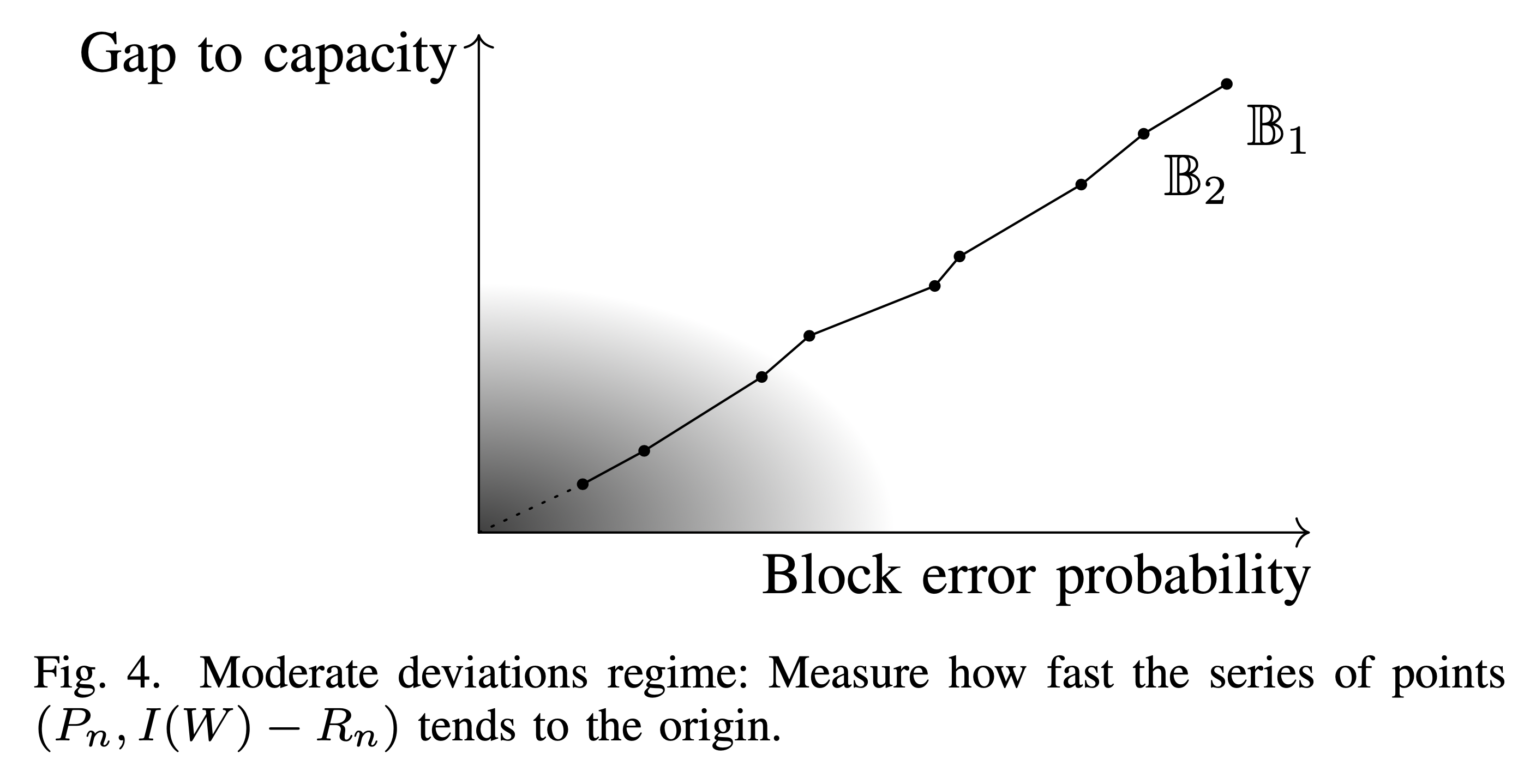

In the early days, my research focuses on the moderate deviations principle (MDP) paradigm of noisy-channel coding. MDP addresses the asymptotic trade-offs among block length $N$, error probability $P_e$, and code rate $R$. It is easy to show that

for some positive numbers $\pi$ and $\rho$. Except that the region of achievable $(\pi, \rho)$-pairs as $N \to \infty$ is hard to characterize.

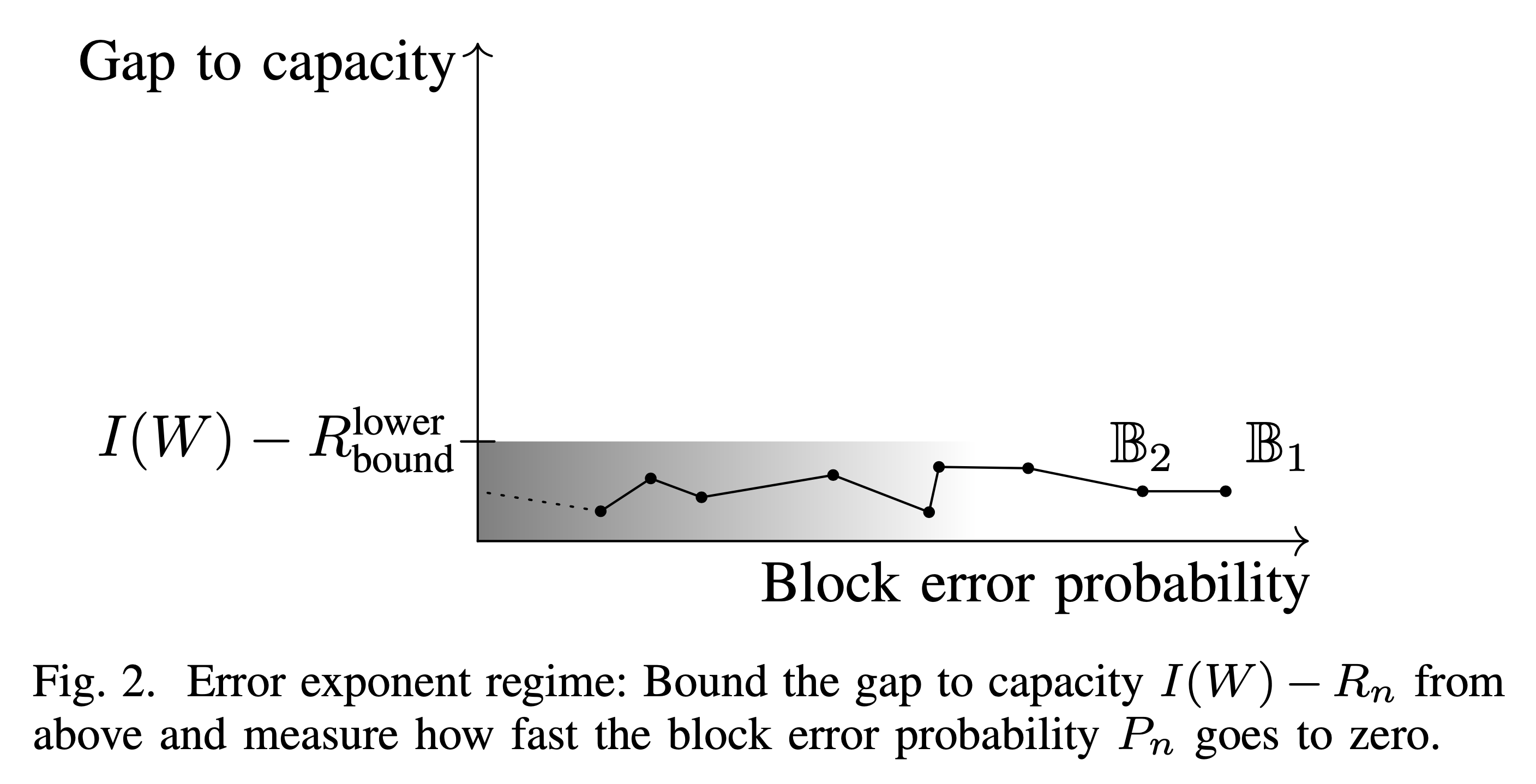

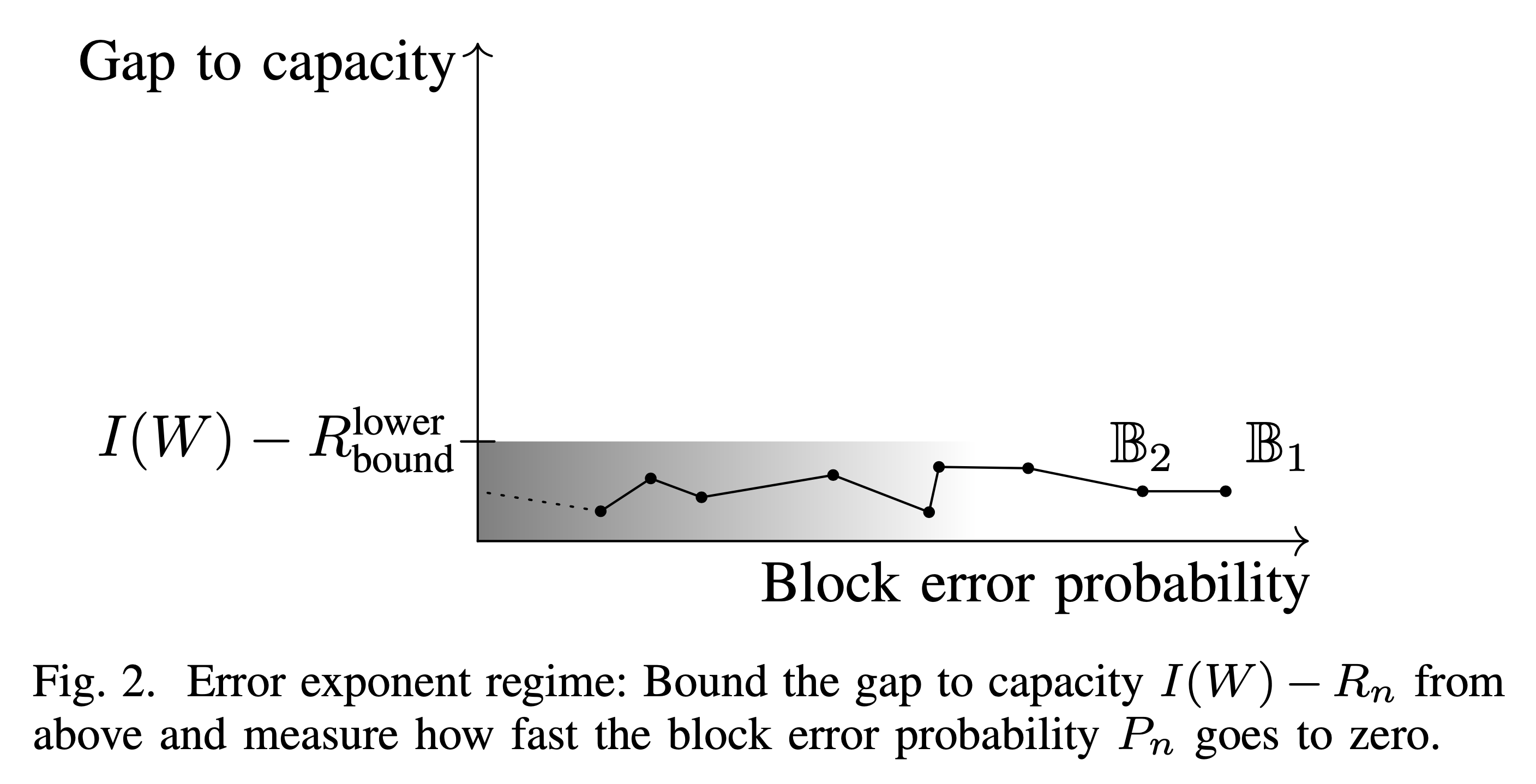

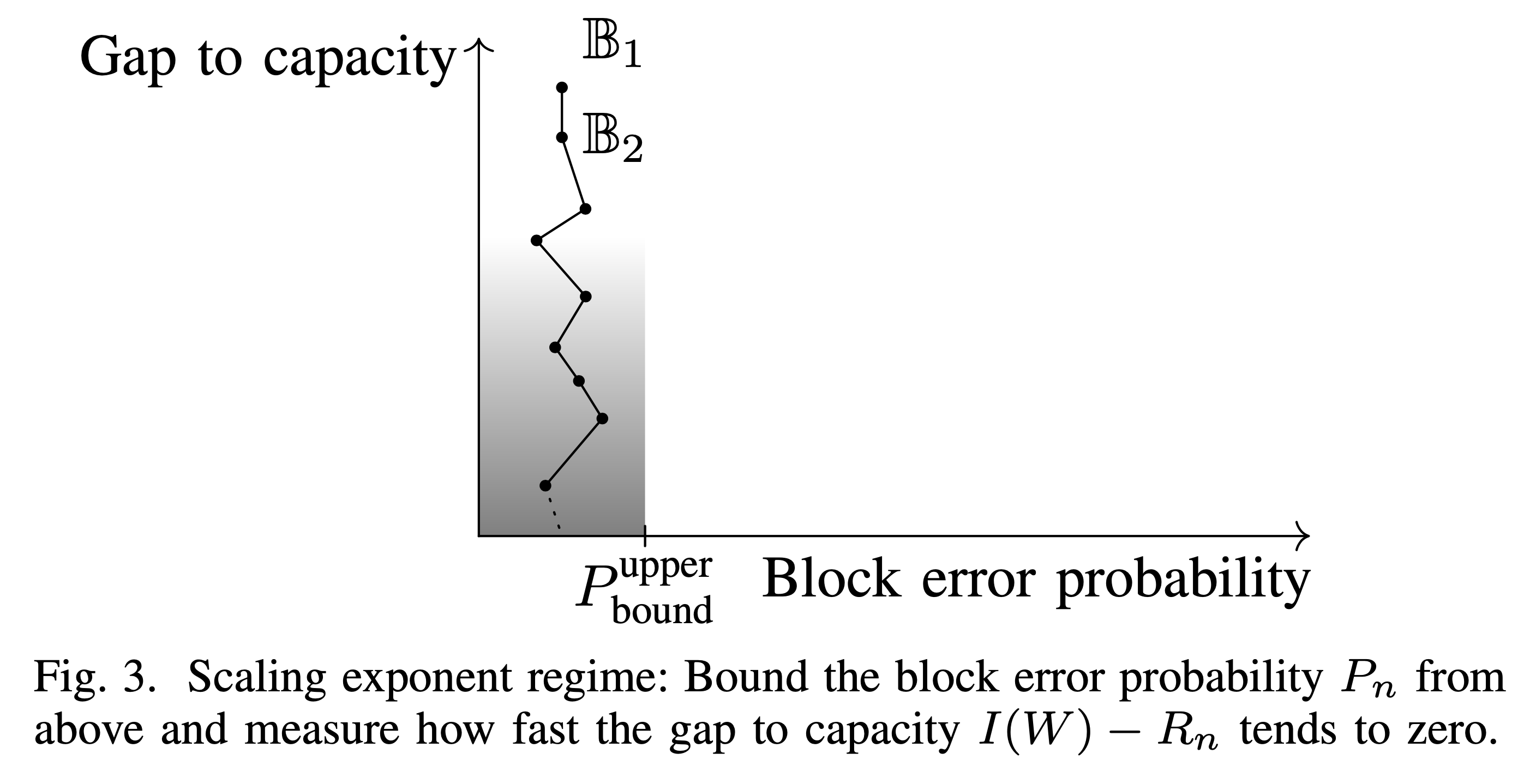

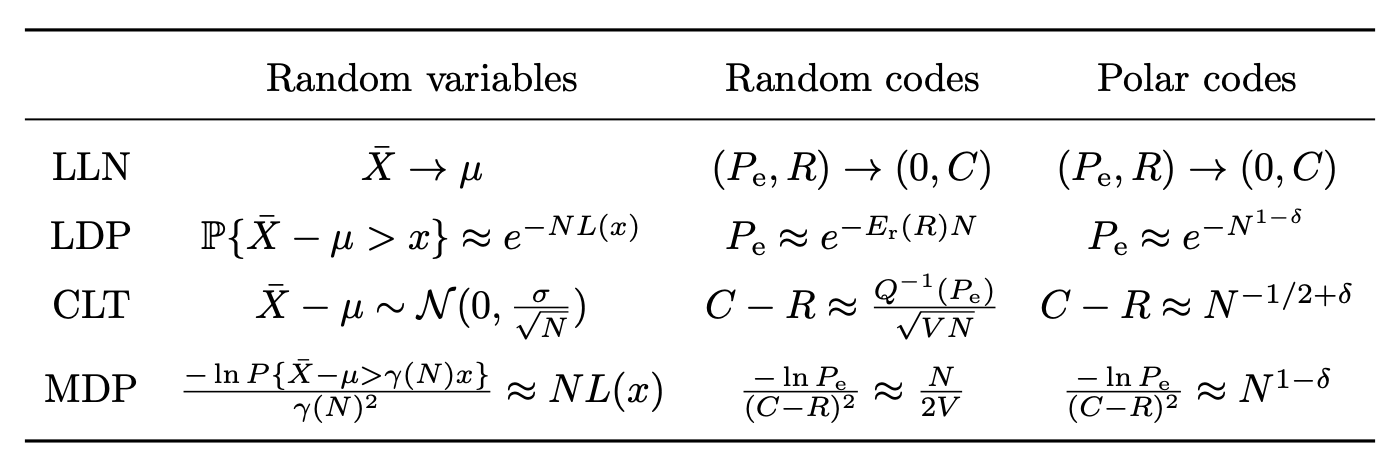

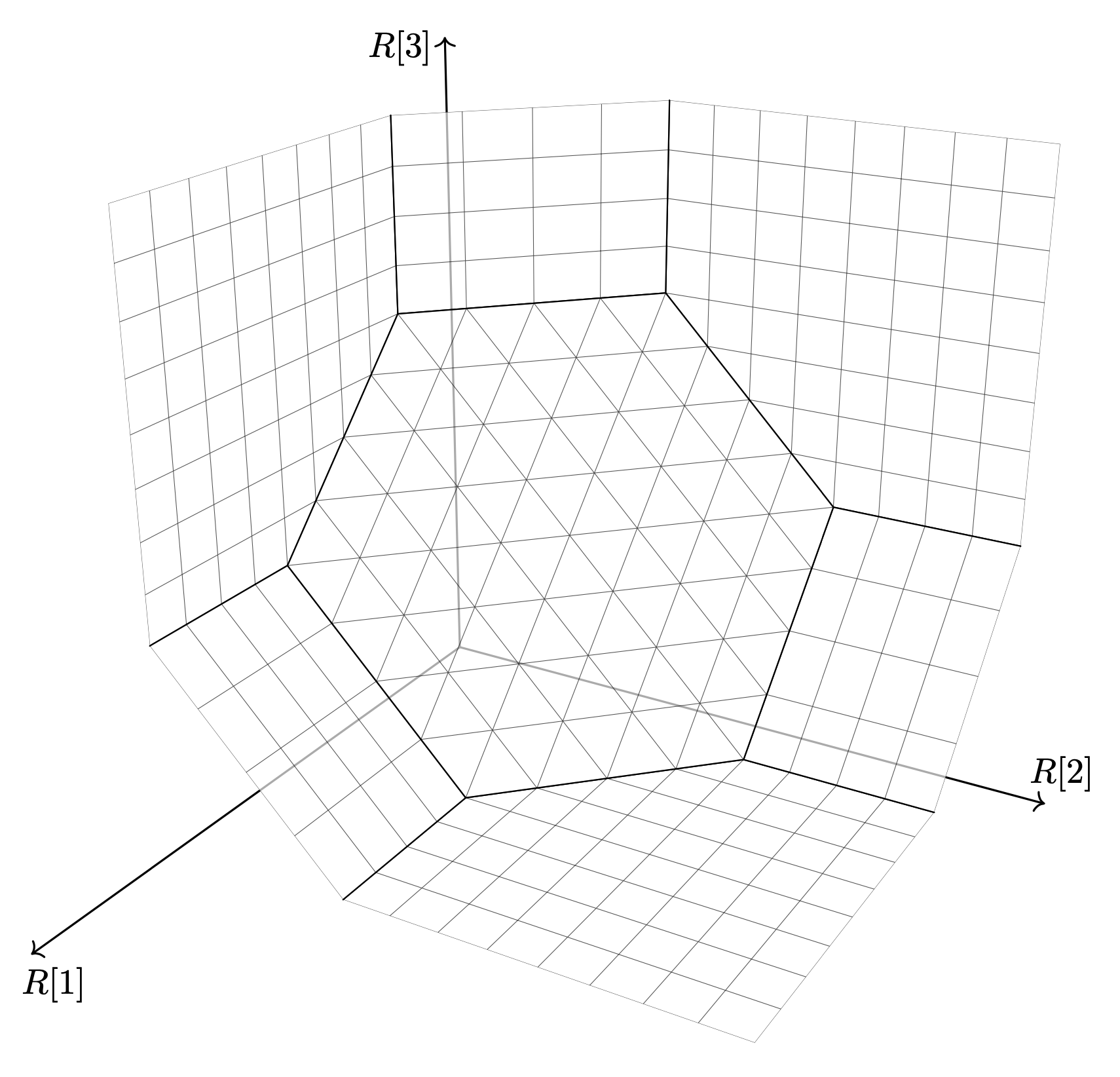

The MDP paradigm is a combination of the large deviations principle (LDP) paradigm and the central limit theorem (CLT) paradigm. In LDP, one cares about the asymptotic behavior of $P_e$ but not so much about $R$. In the CLT paradigm, it is the opposite, that the asymptotic behavior of $R$ is studied and $P_e$ more or less stays constant. Both LDP and CLT are popular topics in coding community, especially for random codes. My research differs with two twists, (1) MDP studies the joint trade-offs, and (2) polar codes are low-complexity codes. The following figures from [ModerDevia18] illustrate the situation.

I got into this topic because of Mondelli, Hassani, and Urbanke’s work Unified Scaling of Polar Codes: Error Exponent, Scaling Exponent, Moderate Deviations, and Error Floors [MHU16]. This work shows that the scaling exponent of polar coding is $\mu \approx 3.627$ over binary erasure channels (BECs) and $\mu < 4.714$ over binary memoryless symmetric (BMS) channels. Here, the scaling exponent $\mu$ is the lowest value $1/\rho$ can take if $P_e$ is a constant. On top of that, this works gives a characterization of the region of $(\pi, \rho)$-pairs. However, this region does not touch the point $(0, 1/3.627)$ for the BEC case or $(0, 1/4.714)$ for the BMS case, which suggests that something nontrivial happens when we make constant $P_e$ exponential decay.

My work [ModerDevia18] addresses the mismatch and shows that, using a complicated combinatorial counting method, the region of $(\pi, \rho)$-pairs will touch $(0, 1/3.627)$. Hence the slogan moderate deviations recovers the scaling exponent.

While [ModerDevia18] deals with classical polar codes as constructed in Arıkan’s original paper, [LargeDevia18] extends this theory to a wide class of polar codes. Given a kernel $K$, its scaling exponent $\mu$, and its partial distances, we are able to predict how polar codes constructed using $K$ will behave in terms of the region of $(\pi, \rho)$-pairs. Remark: This result says that it is easy to prove MDP given an estimate of $\mu$. But $\mu$ is usually difficult to estimate.

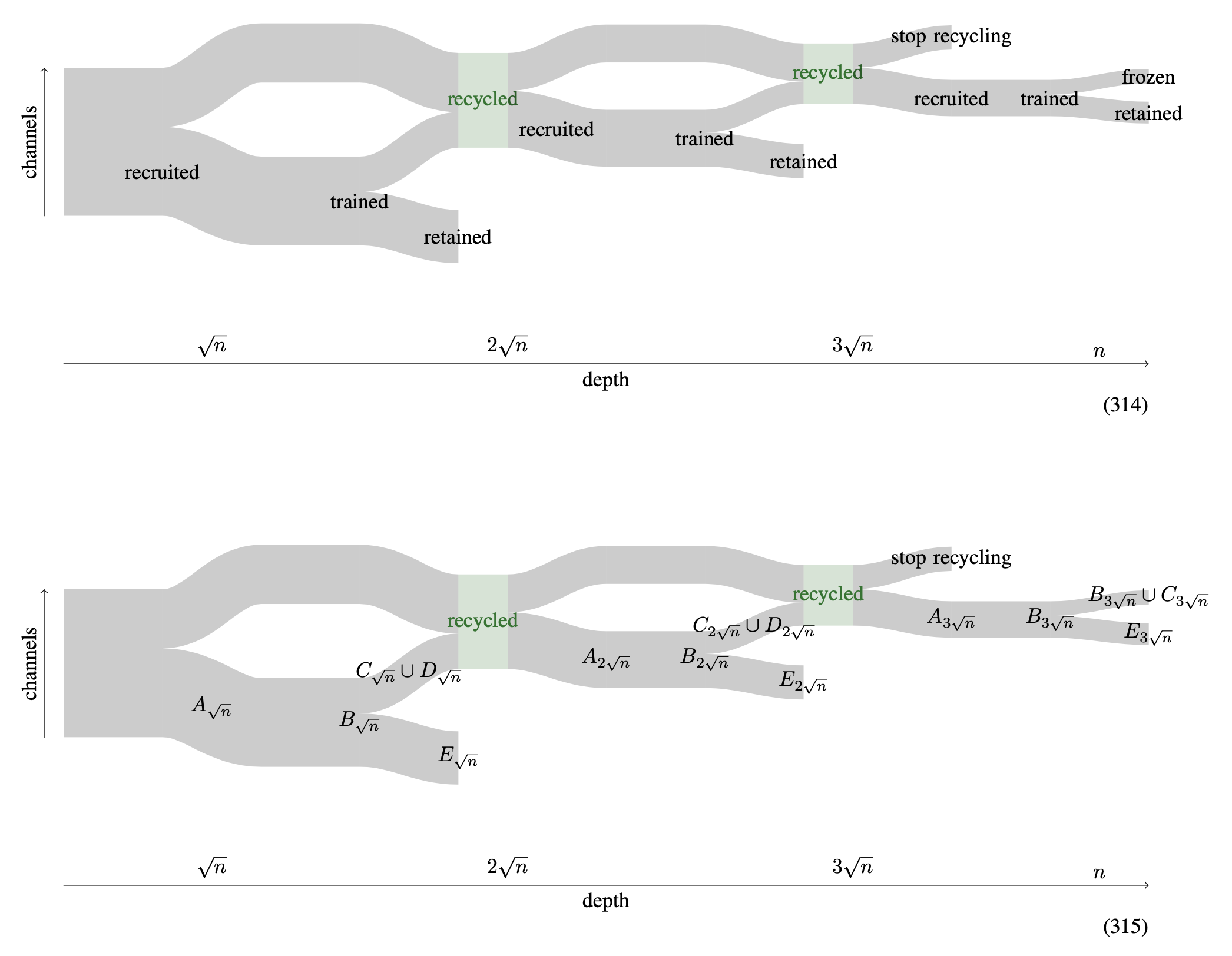

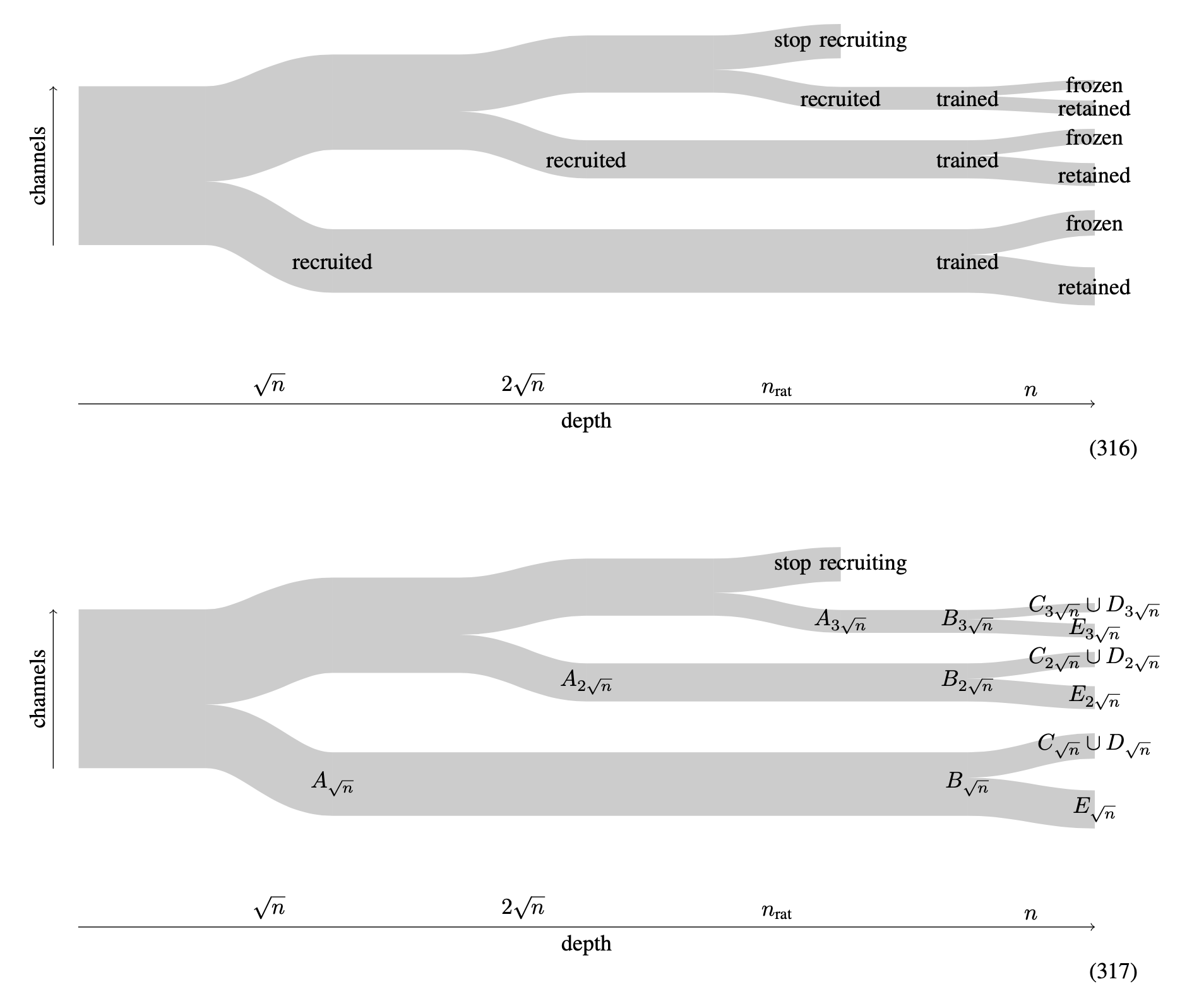

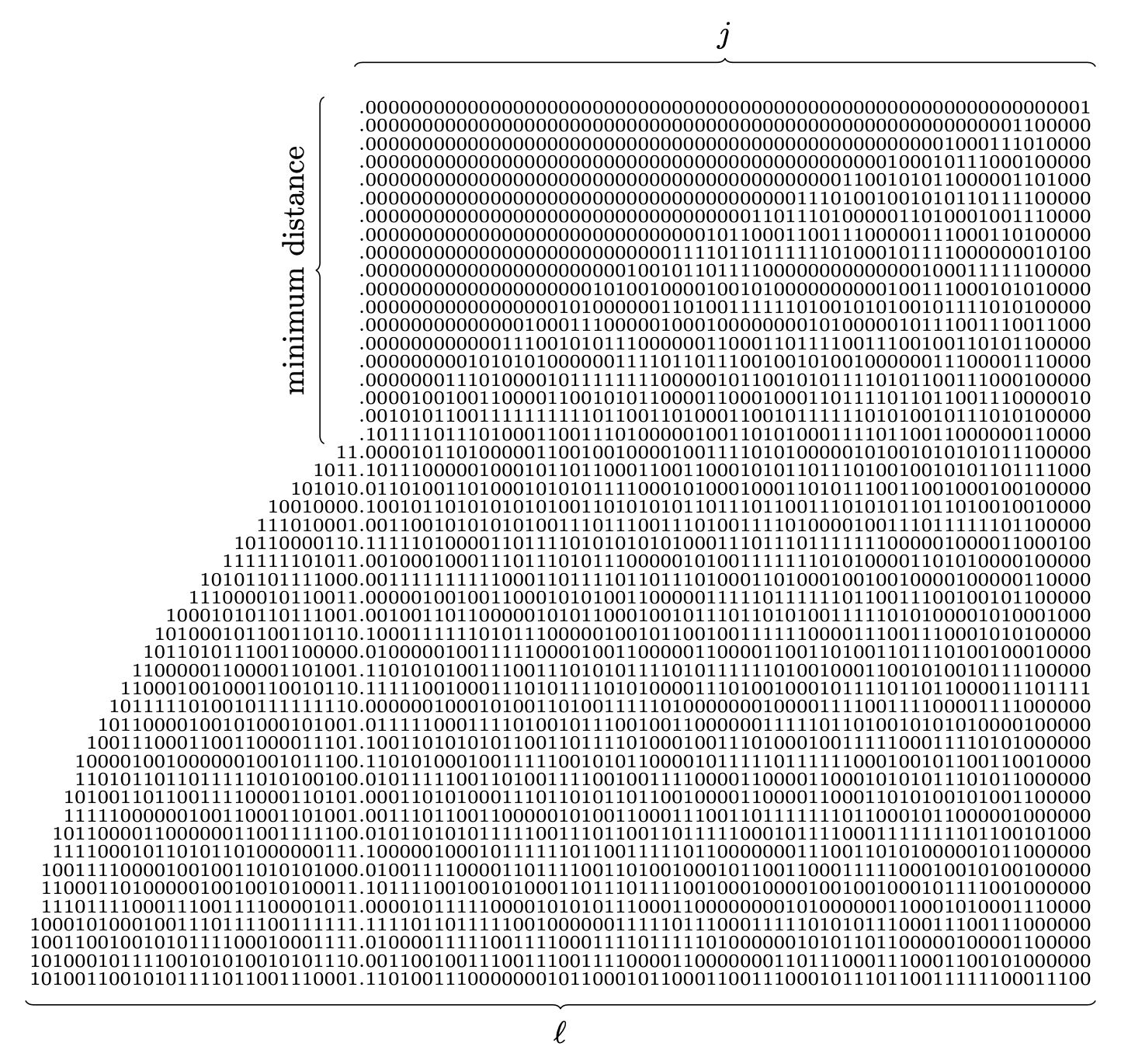

Next, I move on to encoding and decoding complexities. The following sequence of figures from [LoglogTime18] demonstrate how channel evolution works in ordinary polar codes.

This is generalized to a more general tree-controlled circuit.

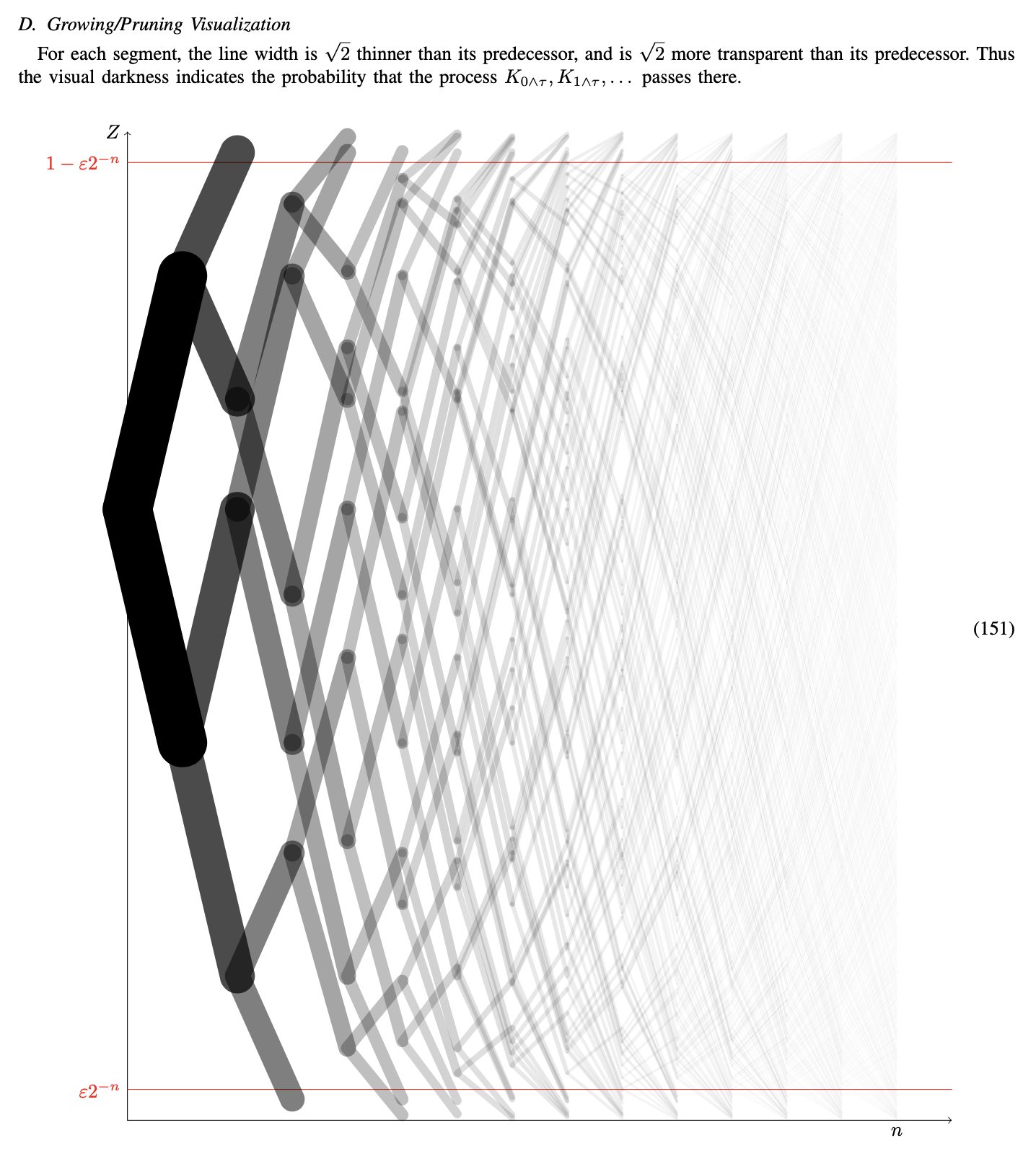

The idea is that, if we would like to tolerate slightly worse $P_e$ and $R$, we can omit some of the green and purple boxes. This reduces the encoding and decoding complexities from $O(\log N)$ per information bit to $O(\log(\log N))$ per information bit.By worse $P_e$ we mean that $P_e$ scales as $N^{-1/5}$. By worse $R$ we that mean that $\text{Capacity} - R$ scales as $N^{-1/5}$. Note that the constructed code still achieves capacity, just not as fast as before. Here is a visualization of how many branches are left after pruning.

While [LoglogTime18] deals with BECs, [LoglogTime21] handles arbitrary symmetric $p$-ary channels, where $p$ is any prime. The main theorem in the new paper follows the recipe of the old paper—by tolerating that $P_e$ converges to $0$ slower and that $R$ converges to the capacity slower, we can reduce the complexity to $\log(\log N)$ per information bit.

Note that, in both [LoglogTime18] and [LoglogTime21], codes are constructed with the standard kernel $[^1_1{}^0_1]$; yet the same idea applies if a general kernel $K$ is used. What’s more, the log-log behavior generalizes to arbitrary discrete memoryless channels (DMCs). For general channels, however, the standard kernel $[^1_1{}^0_1]$ does not polarize anymore. So the observation that a general kernel $K$ is compatible with the log-log trick is crucial here.

Now comes my favorite work.

[Hypotenuse21] shows that it is possible to construct codes whose error probabilities and code rates scale like random codes’ and encoding and decoding complexities scale like polar codes’. On the one hand, random codes’ error and rate are considered the optimal. On the other, polar codes’ complexity ($\log N$) is considered low. (Not the lowest possible complexity, as $\log(\log N)$ complexity is possible for general channels and $O(1)$ is possible for BECs.) This result holds for all DMCs, the family of channels Shannon considered in 1948.

For a figurative comparison of the region of $(\pi, \rho)$, see Figure 1 on page 3 of [Hypotenuse21] (or Figure 5.4 on page 57 of [Dissertation21]).

[Dissertation21] is my PhD dissertation. I summarize my earlier works and extend them a little bit.

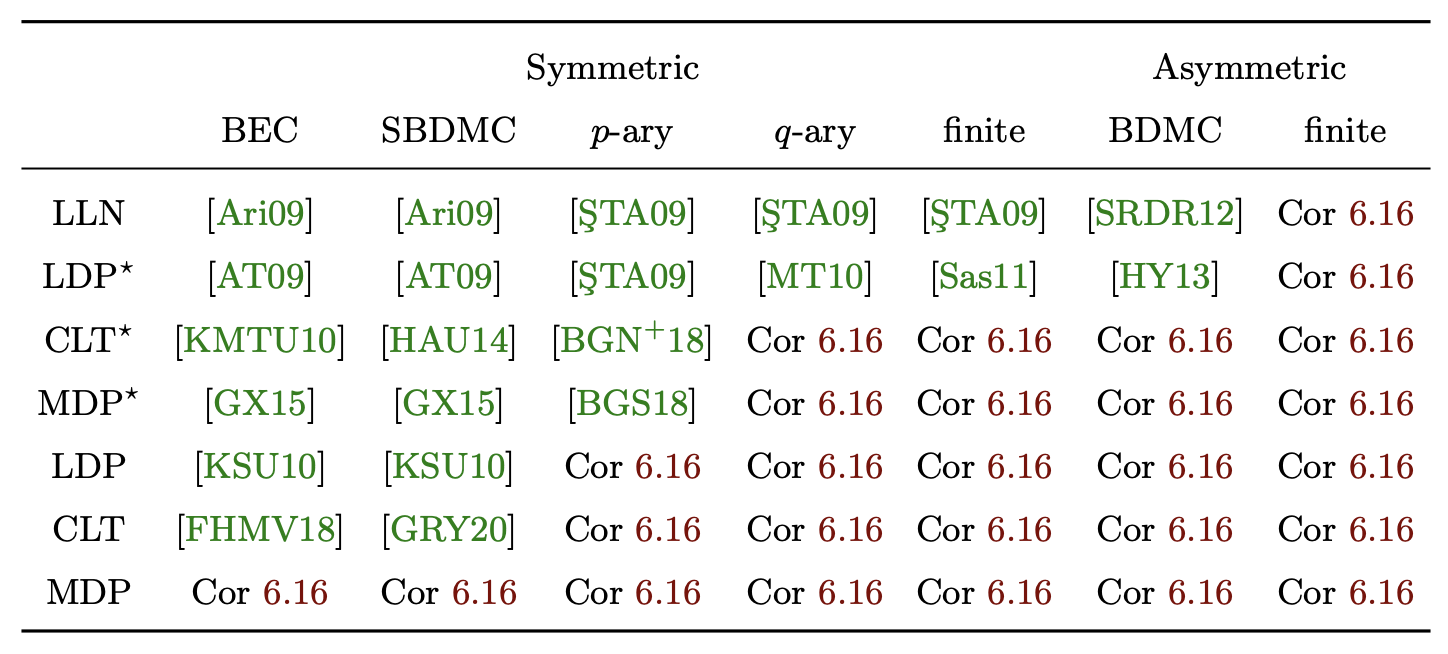

I put a lot of efforts in to my dissertation, especially to figures and tables. The following table is for channels versus goals and references. It is Table 6.1 on page 98.

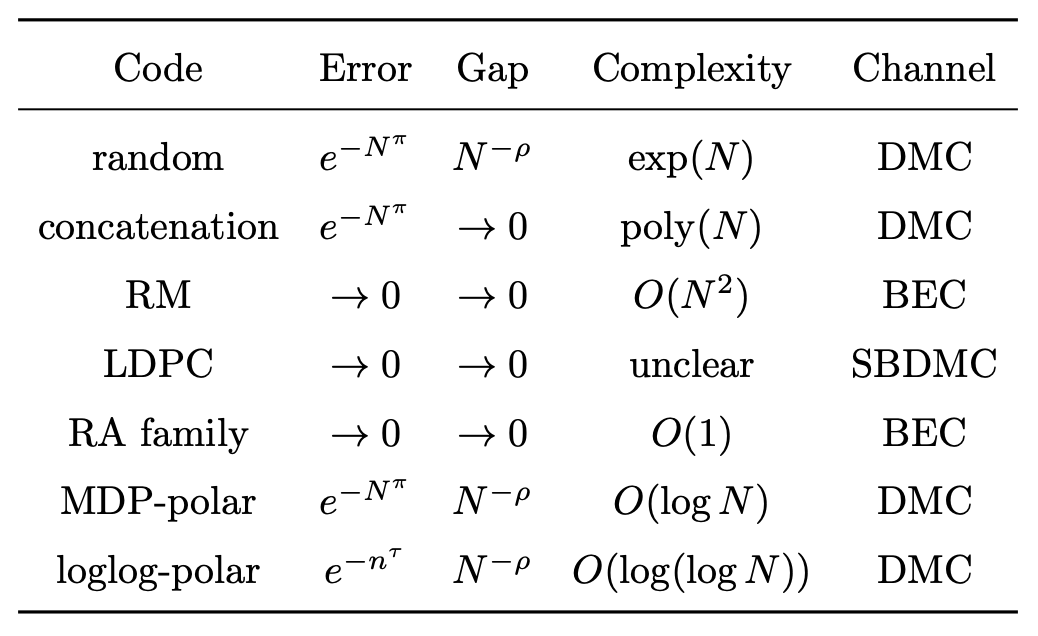

Here is a table for the error–gap–complexity trade-offs of some well-known capacity-achieving codes and the corresponding channels, obtained from Table 7.1 on page 103.

The following table, taken from Table 5.1 on page 55 of [Dissertation21], describes an analog among probability theory, random coding theory, and polar coding theory.

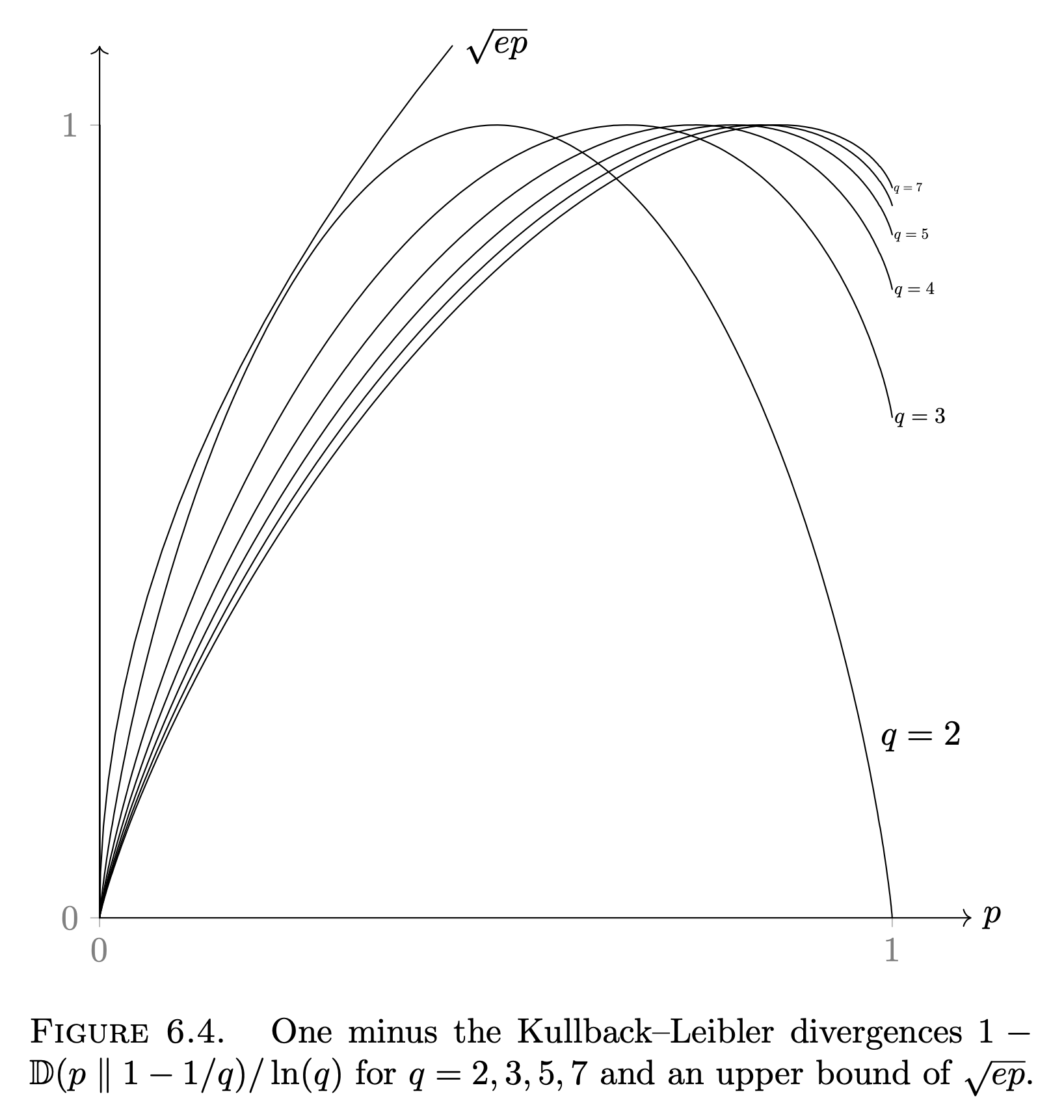

Binomial coefficients recover the binary entropy function; this is used in the study of minimal distances of random codes. This is Figure 6.3 on page 80.

Binary entropy function and the KL divergences that are useful for larger alphabet has a nice upper bound $\sqrt{eq}$. This is on page 82.

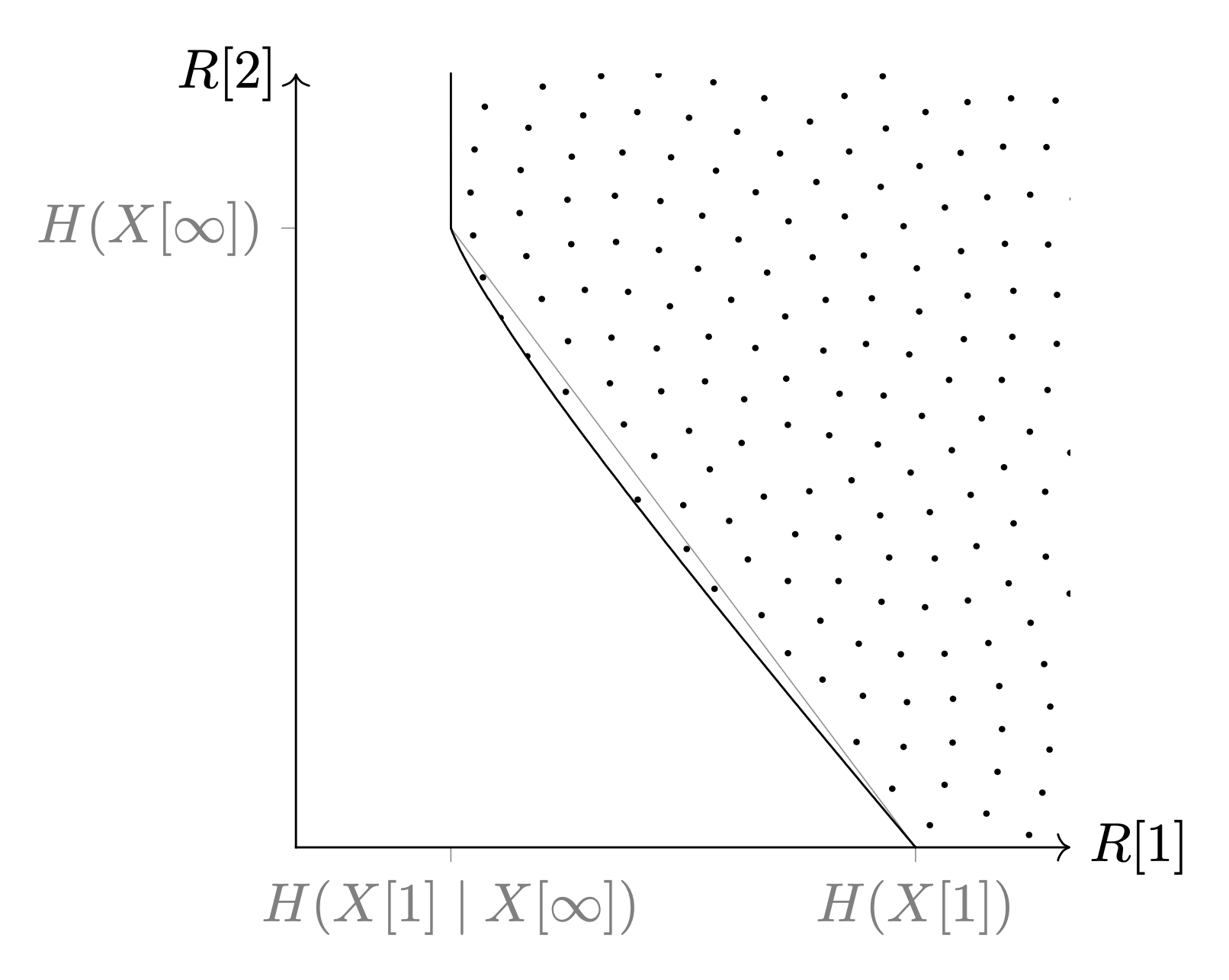

Capacity region for distributed compression. (Page 110)

Capacity region for distributed compression. (Page 113)

Capacity region for multiple access channels. (Page 119)

In the next two works, [Sub-4.7-mu23] and [TetraErase22], I pivot from MDP to CLT. The motivation is that, since any further improvement of MDP will come from improvement of the scaling exponent, I try to attack the latter.

[Sub-4.7-mu23] considers the standard setting of polar code: the standard kernel $[^1_1{}^0_1]$ over BMS channels. Before it was proved in [MHU16] that $\mu < 4.71$. We show that $\mu < 4.63$. This improvement is small, but it delivers a message that considering the iteration one at a time is not enough. In this work, we consider two iterations. We are able to show that, the first iteration will make BMS channel less BSC, and the second iteration will make use of the fact that the non-BSC channels polarize faster.

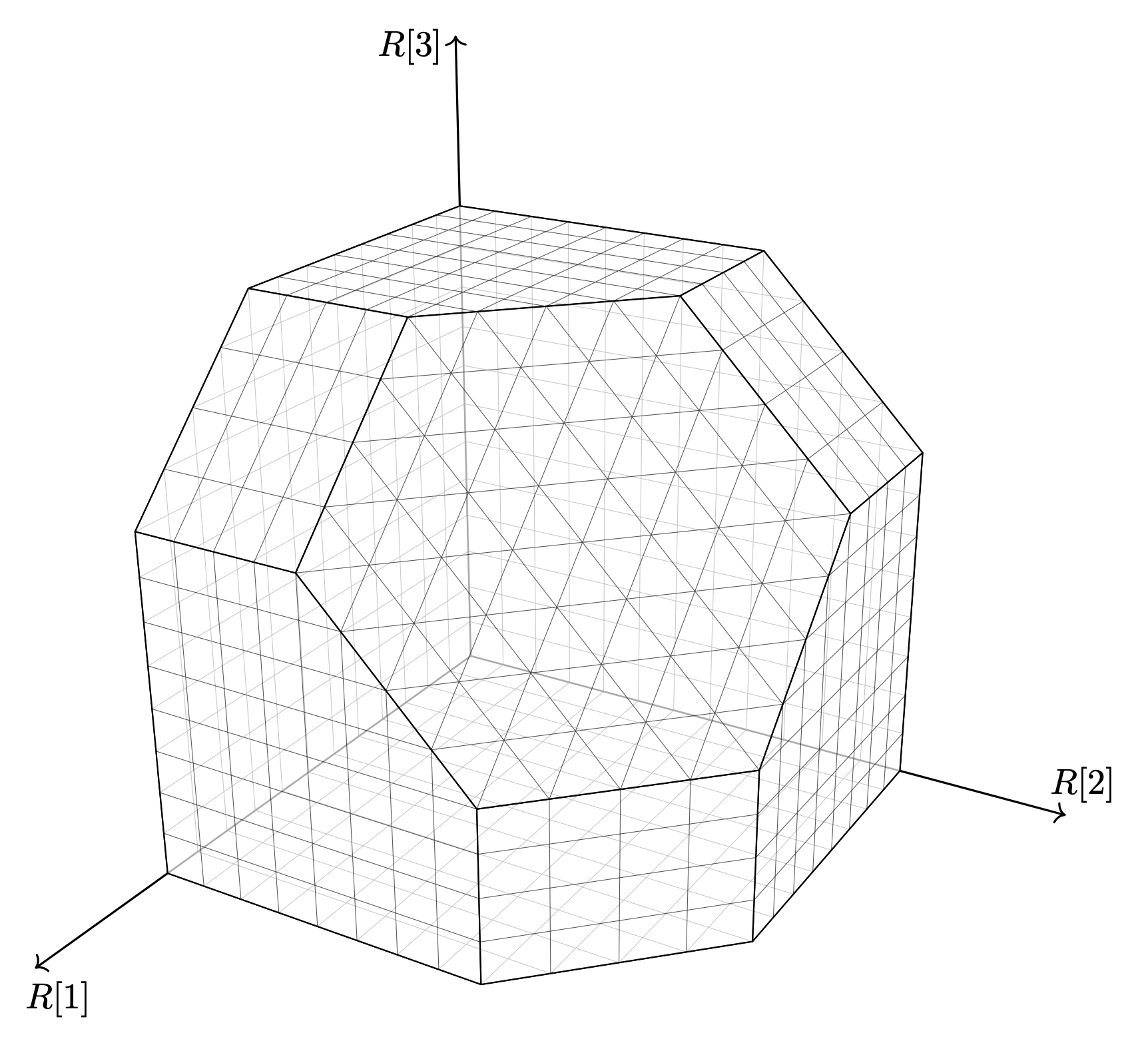

[TetraErase22] is another attempt to improve scaling exponent. But this time the target is BECs. For BECs, it is known for a long time that $\mu \approx 3.627$ [MHU16]. It is also known for a long time that to improve $\mu$, one can use a larger kernel matrix $K$ [FVY19]. We go for another direction: enlarging the alphabet size. We show that, by enlarging the alphabet size from $2$ to $4$, the scaling exponent improves from $3.627$ to $3.3$. It would have take a $20 \times 20$ (linearly interpolated) matrix to achieve the same improvement.

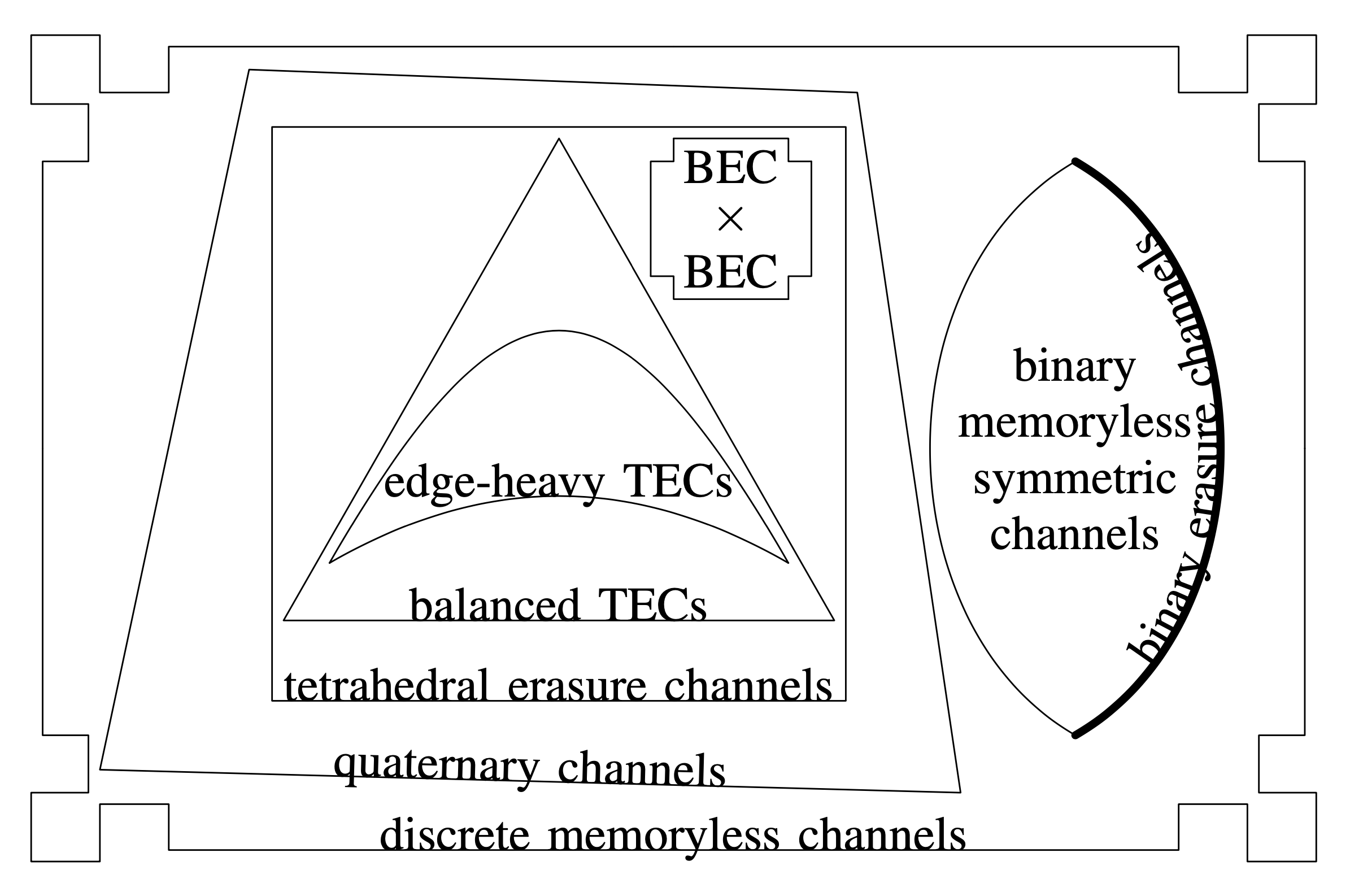

Because in [TetraErase22] we need to bundle two BECs into a TEC (tetrahedron erasure channel) , I made a Euler diagram explaining various classes of channels.